THE CATHOLIC MARTYRS OF RUSSIA

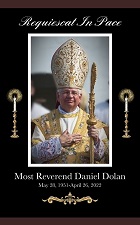

TO THE MEMORY OF FR. CONSTANTINE BUTKEWIECZ,

PRIEST MARTYRED FOR THE CATHOLIC FAITH

HOLY SATURDAY, 1923

The Soviet Government did not begin to show hostility towards the various religious denominations from the very beginning of their rule. They waited and moved with caution; their prosecutions of religion gradually grew in violence. The Bolsheviks at the very beginning had proudly declared to the whole world their determination to respect liberty of conscience in Russia; but this was nothing but a convenient pose which they dropped at the earliest opportunity, and now one of their leaders, Bukharin, says: "It is the task of the communistic party to impress firmly upon the minds of the workers, even upon the most backward, that religion in the past and to-day is one of the most powerful means at the disposal of oppressors for the maintenance of inequality and the exploitation of slavish obedience on behalf of the toilers. Religion and Communism are incompatible both theoretically and practically."

The first religious prosecutions were directed against the Russian State Church. It should be borne in mind that, when the Bolsheviks came into power, they had no mere Holy Synod Church to deal with, a Church secularized to the utmost and subservient to the ruler's will and whim. Instead of this Erastian Church the Bolsheviks had to face a strong religious body, united under one Patriarch, and strong in the newly won sympathies of the masses. The Soviets realized that they would hardly be able to cope with this vigorous institution, consequently they began to use, though with the utmost caution, all the weapons at their disposal for creating interior divisions in the Russian Church. They were fairly successful in bringing about numerous rifts within the Church, and it was no difficult task to dictate their own terms to a divided communion. One part of the Orthodox clergy bowed down under the Soviet yoke, and hence arose the living Red Church, which later was subdivided into two new Churches. The remainder who

could not reconcile either their own principles or the Church's teaching with communistic theories paid the penalty in Soviet dungeons, and their records are not as yet brought to light. But, anyhow, the Soviets got what they wanted from the Orthodox. They rendered them impotent to put any obstacles in the "Red Way."

Next came the turn of the Catholics. As one of the Soviet leaders has put it, they were conscious, and rather uncomfortably conscious, that this "enemy" was of a vastly "different mettle." But even against the Catholic Church they proceeded cautiously and prudently, mainly from political reasons. They were not sure of the issue on the Polish front, and they regarded the Roman Church somewhat in the same way as Polish property. They have changed this point of view since, for now they do not scruple to defy the whole civilized world.

The first open hostilities to Catholics began at Easter, 1919, when several Red Guards made a violent intrusion into some of the Catholic churches of Petrograd and Moscow, interrupted the Mass, and literally dragged the clergy in their vestments from the altars into the Cheka. The few people who attempted to intervene were immediately arrested, but soon released, and the whole thing was carefully hushed up by the Bolsheviks. However, this incident had so aroused religious feeling that the authorities thought it prudent through the Soviet press to attribute the occurrences to an outburst of Russian patriotism - the period was one of severest fighting between Russia and Poland - and any official "egging on" was disclaimed. And yet, three years later, when the Catholic clergy were called on for trial, this incident was brought against them as the first instance of their "exciting the people to rebellion against the Soviets," though it was largely the people themselves who had taken the initiative of defending the sanctuary threatened with profanation by the Red Guards.

The real trend of the Soviet religious policy, especially towards the Catholics, grew plainer in the winter of 1919, when the question began to be discussed at their "agitation meetings." At one of these a Communist speaker openly declared that "at the beginning of our rule we had two formidable enemies to deal with: one was the Tzar, whom we have since rendered impotent to harm our cause; and the other is the Roman Catholic Church, headed by a Pope in Rome who is the avowed enemy of all liberty and equality."

One of the first prohibitory measures was the decree which laid a veto on all kind of religious instruction whether private or public. The Catholic clergy, whom it concerned most, had but one answer to give to this decree, and they did not hesitate to give it from the pulpits: "We hold our authority to teach from our Lord Jesus Christ and not from any temporal power. If our Master were to issue such a decree, our first duty would be to render him prompt obedience; but we cannot neglect our duties, much loss discontinue them at the bidding of any temporal power." Naturally, this answer was later imputed to them as criminal incitement of the parishioners towards disobeying all decrees of the Soviets. Nevertheless, this decree caused the clergy to suspend public instruction for a time, as it was considered best to act with utmost prudence, but they never stopped instructing children in private. This, too, was reported later, and alleged as a State crime.

One of the Soviet's next blows was to forbid the Monday lectures in Petrograd. The Communists could not very well forbid them as meetings, since such a measure would appear to encroach upon the liberties granted by themselves; but the local Soviet used to suspend them for a time under various pretexts, as they sometimes wanted the hall for themselves. All these prohibitions, however, were temporary until the spring of 1923, when the lectures were finally forbidden.

But the real trouble began in 1922. Till then, occasional individual arrests of the clergy took place, and the Government's attitude towards the Church was more or less menacing, but no systematic onslaught was directed against Catholics as such.

In December, 1922, all the Catholic Churches in Petrograd and Moscow were closed by the authorities, and the clergy with but few exceptions found themselves summoned for trial before the High Revolutionary Tribunal. The causes leading to that trial were numerous and rather tangled. Furthermore, the grievances against the clergy were mostly of some four years standing. The two main causes were these; (1) the Church Property Agreement; (2) Religious Education. The general charge was simply rebellion and unwillingness to submit to the Government, and attempting to stir up rebellion among their parishioners; in short, anti-government propaganda.

Previous to these proceedings, the ransacking of the Catholic churches throughout Russia took place.

It happened in the summer of 1922. There were incidents connected with these "sequestrations of church plate" which the Soviets would not care to bring to light. These "sequestrations" brought in reality very scanty material results. The chief object held in view by the authorities was to inflict the greatest possible humiliation on the faithful. In most cases these raids were accompanied by wild outbursts of most abject and vulgar profanation hardly ever checked by the higher officials who were invariably present at such proceedings.

I am able to record a few incidents which show the extent of hatred and fear that the Bolsheviks feel towards the Catholic Church. In a little suburban church, the Red hooligans asked the priest, a very aged man, to give up the keys of the Tabernacle, which, as they thought, "held the greatest treasure of the Catholics." The old priest did not answer, but went up to the altar and began to pray before the sanctuary. He knew himself to be helpless, as the Reds had chosen the middle of the night to make their church raid, so that no one might be called to his aid. Nor would aid have been of use, as the Reds had had express orders to shoot down all and any who resisted. Seeing that the old priest was not likely to give them the keys required, the brigands knocked him down, and while he was rolling on the ground, they sent for a locksmith, broke open the Tabernacle, threw the Host on the floor, trampled it under their feet, and left the church, swearing loudly because the stolen chalice proved to be of no great monetary value. The old priest did not long survive the shock, for a few hours afterwards he was found lying dead at the altar steps.

Another instance took place in the summer of 1922 at St Catherine's in Petrograd, the last church to suffer from the sequestration, because of its immense popularity. Finally came the sequestration day appointed by the local Soviet, who politely said that they would come in the afternoon, as they were aware that there were services going on in the morning, and they would not like "to disturb them."

As a matter of fact, they turned up a little after 11 a.m., when the last Mass was not yet finished. There was no other priest on the premises except the celebrant, and they were consequently told by the sacristan to wait, as they were not authorized to start proceedings without at least one priest being present. So the Red gentlemen waited in the vestry, grumbling at the delay as they stood in their red high-peaked caps. When Mass was over, the priest came out into the vestry and quietly unvested himself, washed his hands, said his prayers, and appeared to ignore their presence.

Then their patience forsook them, and they roughly demanded the vestry keys. Their next request was to "have the people cleared out of the church." The priest ignored the first request, and to the second he replied: "I am a priest and not a policeman; my business is to make people come into God's churches, not to ask them to leave." They shrugged their shoulders and set themselves to drive the people out of church. It happened to be a Thursday, and the congregation mostly consisted of young women and girls, members of the Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament, who had their weekly Mass on that day. They all came into the vestry before leaving the church, and asked if they should go and leave the priest alone and unaided now that trouble was coming on. He smiled and waved his hand towards the High Altar: "You need not be afraid. God will shield his own." The Reds heard these words and inferred that the counter-revolution was lurking everywhere in Catholic churches and that there must be forces hidden behind the altar.

So the women left the church, but they all remained standing in the yard outside, most of them weeping. A few people who had an official right to be present as members of the parochial committee, remained in the vestry. The priest stood motionless and silent. He never said a word to the Reds after his first dignified rejoinder. Having cleared the church and locked it from the inside, the Soviet emissaries returned to the vestry, and again requested the priest to deliver the keys to them. Still no response came.

Then the sacristan found the keys and put them on a table. They seized them eagerly, and the pillaging duly began. They did not find much, and only took about 15 pounds worth of silver, mostly in chalices. They also took a beautiful monstrance, deposited at St Catherine's, which was not the parish property. One of the members of the parochial committee intervened, volunteering to give written evidence of the truth of his statement, but no attention was paid to him. Having thoroughly examined every nook and corner of the vestry they demanded pen and ink, and were already on the point of drawing up the protocol when a member of their party, who had been a Catholic before he turned Communist, stopped them.

"Comrades," he said, "we have not finished. These people always keep their most precious chalice, often studded with gems, in a cupboard on the altar; but it is generally locked, for fear of being robbed. The priests keep it so to deceive people and to conceal their avarice. They say they keep their God there, and make people genuflect to him, but it matters little whether they have their God or our devil there, if the chalice is worth having."

Then the leader again asked the priest: "Now will you give us the key?" The Father was silent. "Comrades, let us fetch a locksmith and have it broken open," cried another. And then the priest stepped slowly back and barred with his body the little door which led from the vestry into the Church, in calm, dignified tones he spoke to his parishioners: "Children, let us go and pray, we will not see our sanctuary profaned. If need be, we can lay our bodies on the altar steps." And the little group resolutely moved towards the altar door.

The comrades laughed uneasily, and stopped them. "Citizens, we are not going to start bloodshed, keep what you like. Only we shall have to put it into the protocol," which they did; but the priest's words to his flock were taken to mean: "Let us go and die fighting on the altar steps."

Similar scenes happened all over Russia. The Bolsheviks may have had some material excuse for ransacking the Orthodox churches, as these contained treasures, but they had none with the Catholic churches. And they seemed to realize it themselves, as later on they said they were only trying to pick quarrels with the clergy and laity.

The sequestration of Church plate was over; the question of Church property, both movable and immovable, remained. This was a thorny matter for both sides, and the Soviets began to tackle it in a most offensive way. They first tried to have it decided without any intervention of the clergy. Substantially, all the parochial committees were to sign an agreement by which the administration of the parochial property was to be taken altogether out of the hands of the local clergy and handed over to a lay-committee supervised by a local Soviet. The parishioners were called upon to sign this agreement without delay, as the Soviets said that this measure only tended for their own ultimate good, "since it liberated them from the clerical yoke." At first mild means were used. People were reasoned with and shown the evident advantages of the new order of things, but it would not work. The bewildered parishioners turned to the clergy for advice, in spite of the severe admonitions and prohibitions of the Soviets. The clergy had, indeed, but one answer to give: "Wait till Rome decides the matter; we cannot do it." So the people waited, not wishing to sign the agreement.

This became irksome to the Soviets. In July, 1922, they started organizing parochial meetings in order to bring the question to a quicker decision, but there was the same result. The parochial representatives would not swerve in their resolution "to await the decision of Rome." The Soviets' patience gave way at last. They declared "adherence to Rome was treason in disguise," and threatened to close all the churches, unless their request was promptly complied with. But the parishioners' attitude was unaltered. It ended in the closing of all the churches in December, 1922. For two or three months afterwards the services were conducted in private, but soon even this had to be suspended for fear of penalties, and in Lent, 1923, all the clergy of Petrograd and Moscow were brought to trial.

The charges against them were numerous. The following is a condensed summary of them: "The clergy concerned exploited in a shameless and vulgar way the base religious superstitions of the Catholic population of Petrograd and Moscow, and used all the means in their power to win over the most ignorant among the Russian Orthodox; they used for propaganda their pulpits and private meetings, inciting to non-execution of the decrees of the Soviets as to the nationalization and conservation as well as utilization of all ecclesiastical property, the registration of births, deaths, and marriages, etc. They also brought elements of political propaganda into their activity by their constant appeals to Rome and Poland, though these appeals were always made under sham ecclesiastical pretexts. They were found guilty of having justified these and many other criminal acts by reference to the canonical laws of the Roman Catholic Church, and of having knowingly given a false interpretation of certain legislative acts of the Government; of having worked upon the religious conscience of the faithful in a way liable to provoke an attitude hostile to the Soviet power which led to troubles with the parishioners of the Petrograd and Moscow churches upon the conclusion of agreements relating to the use of church property, to the non-execution of the proposals of the Government authorities concerning the ways of its use, and also to an almost general opposition to the closing of churches which occurred in Petrograd during 1922, and which was accompanied by an open disobedience of the legal authority, crimes foreseen by articles 63 and 119 of the Penal Code." This is but a short abrege of the charges imputed to the Catholic clergy of Russia.

Of course, from a Soviet standpoint these charges are true. The clergy could assume no other attitude towards the Government of Lenin and Trotzky than which they had through all these years, for otherwise they would not be what they ought to be. But there is one falsehood which stands out clear to anyone who has watched the situation through the last few years. None of the clergy could be accused of inciting people to rebellion against the Government. On the contrary, they made gigantic efforts to hold the people back from violence and hostility towards the Soviets whenever their parishioners' patience gave way. They constantly preached forbearance and love. Even when religious hatred and persecution began to appear among the Government leaders, their attitude remained unswerving. To quote from a letter written by one of the priests on the eve of their trial in February, 1923: "At the moment of writing, there are processions parading the streets, denouncing 'the false divinity of Christ' and burning our Lord's and our Lady's images. It strikes me that they would not spend so much time and energy if they were not sure in their hearts of the strength and truth of Christianity. They feel it in spite of their not wishing to feel it. Hence their fury because they are conscious of being at grips with a force beyond their own strength. What can we do, you ask? We can only pray for them because they are blind and because they hate us. They expect us to hate them in return, but we cannot, and we would not if we could." Another letter, the last letter received from them: "We are to be summoned tomorrow. We are in God's hands, and so all will be well even through the darkness. It is for some better end." These last letters of men about to meet certain death are one more proof "that our faith is not vain, and our hope also is not vain."

What conclusion should be drawn from all this? What have the Soviets achieved by torturing and persecuting clergy and laity who chose to remain loyal to their faith? They seem to have succeeded in crushing the Church in Russia. All the clergy are in prison, with their lives forfeit; all the churches are closed; the laity are cowed and frightened out of their lives by incessant torrents of blood streaming all around them. Have not the Soviets been successful?

Yet, whilst pursuing this violent policy, they seem to be blind to the fact that by these acts they are attacking something of great international importance and that they are in danger of having the mass of religious faith throughout the world welded together in one block of solid resistance. Russia's Catholic churches were her last safeguards of morality and spiritual cleanliness. There is nothing else left to support the country. Is it likely to draw strength from the nebulous theories of Communism subversive of all that purifies, elevates and fortifies the soul and mind?

The Soviets have determined to crush the Catholic Church, and they are boasting of their apparent triumph; and yet the spirit of faith is not dead: it cannot die. It lives on. Its strength lies in the same Christ like forgiveness with which for four dreary years the clergy and laity met and braved the onslaught of the enemy. Love is stronger than hate, and will ultimately prevail (p. 84-98).

THE UNKNOWN CATHOLIC MARTYRS OF RUSSIA

THESE facts have come to light but recently. It was in the summer of 1921. There was a little village near Petrograd, along the Petrograd-Viborg Railway. This village once had a Lithuanian asylum for orphans; hence there was a Catholic church in that place. Soon after the Revolution the asylum was closed, as there were no funds to keep it going, and the priest in charge of the little church had to leave. Yet a few Catholic families remained on in the village.

During the next four years the place underwent many a vicissitude, coming alternately into the hands of the Whites and the Reds. After all hostilities were over, the Reds settled there, and the village resumed more or less of its former tranquility, but its inhabitants missed their little church.

The village was naturally brought to rack and ruin during those four disastrous years. Scarcely any houses were fit to live in, whilst the Reds had to keep a considerable garrison there in view of the situation of the village being close to the Finnish frontier. But there was no living accommodation, and at last the authorities resolved to turn both the asylum and its church into barracks. As these buildings were barred and locked, it was decided that the doors should be forced open.

On the eve of the day appointed for the carrying out of this plan, a few Red soldiers sat in the village public house, discussing the details of its execution. They were overheard by some children i.e., three boys who happened to belong to the few Catholic families of the place. The boys were all of them big enough to remember how their mothers used to take them into the little church and teach them to genuflect before the altar, saying that "Jesus lived there." The children grasped the idea that "Jesus' house was to be insulted," as they knew well what the Red soldiers were like. The boys did not know that with the closing of the church the Blessed Sacrament had been removed. Their minds clung to the old associations, and they resolved to do all they could "to shield Jesus."

The children found out that the raid would take place in the small hours of the following morning. Accordingly, they began to watch from midnight on. They crept into the old church through a window which for some unknown reason was left half open, and overlooked the yard of one of the houses. A sister of one of the boys joined them, as she was as eager as her brother and his friends to "shield the dear, loving Jesus."

The children kept their brave watch all through the hours of the night, crouched at the altar steps, and early in the morning the door was broken open and the Reds came in. When they saw the children, at first they gruffly told them to be off, as this was no place for them. The children remained where they were, and the Reds threatened to fire on them. The boys replied they would not suffer their dear Jesus to be insulted, and that they would remain there. The soldiers, most of them more than half tipsy, began to shoot at the children, and two of them immediately fell. Then the soldiers told the remaining boy and his sister to "clear out," but the boy's only answer was to bar the way to the altar steps with his body.

A few minutes later he was carried out of the church, bleeding but smiling. "We have shielded Jesus, they did not dare to touch him," he told his mother when they brought him home.

They shielded Jesus.

The little boy died a few hours afterwards, but he lived long enough to say that he had seen Jesus standing smiling and radiant, on the altar steps, and stretching his hands in benediction on the fallen bodies of the children who laid down their little lives to shield his Tabernacle. And the soldiers saw him, too, but they were terrified; to them he did not appear smiling, so they fled screaming that the place was haunted by the devil. And the boy died radiant, saying: "We have shielded Jesus." (p. 128-130).

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN RUSSIA TODAY

By MARTHA EDITH ALMEDINGEN, B.A.

A Spiritual Daughter of Mgr. Butkewiecz

LONDON

BURNS OATES & WASHBOURNE LTD.

28 ORCHARD STREET 8-10 PATERNOSTER ROW

W.l E.C. 4

AND AT MANCHESTER, BIRMINGHAM AND GLASGOW

1923

NIHIL OBSTAT: F. Thomas Bergh, O.S.B., Censor Deputatus.

IMPRIMATUR: Edm. Can. Surmont, Vicarius Generalis,

Westmonasterii, Die 23 Junii,1923.

p. 84-98, 128-130

|